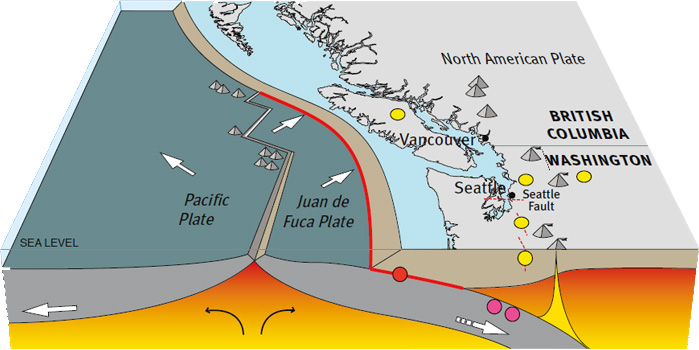

Odd, in that while earthquakes and tsunamis were a well known fact of life, there had been no temblor prior to the giant wave crashing ashore, a 16-footer that instantaneously destroyed 13 homes, triggered a fire that burned 20 more structures and sent villagers fleeing to higher ground to escape the frigid waters and all the detritus being pushed at frightening speed their way. In the seaport town of Kuwagasaki on Japan's north coast, the local magistrate recorded the odd event. On the far side of the Pacific Ocean in a country still reeling from one of the most violent earthquakes in modern history, a tsunami came ashore around midnight Jan. We now know precisely the last time an earthquake of such magnitude occurred along Cascadia's Fault. The colliding edges of the plates are locked, however, and when enough pressure builds, they slip suddenly. It is here that the oceanic Juan de Fuca Plate pushes toward and underneath the North American Plate at a rate of 40 millimetres per year - about the growth rate of your fingernails. In 10,000 years of Kwakiutl occupation at or near Namu, some 20 magnitude 9 earthquakes have occurred, one every 500 years or so, quakes that ripped the entire length of what is today called Cascadia's Fault, a crack on the sea-bottom roughly 50 kilometres off of the north end of Vancouver Island and arcing southeast and then nearly due south to a point 1,100 kilometres away in northern California. Which is why veteran documentary filmmaker and writer Jerry Thompson has stepped forward with a timely warning of the monster that will - not may - strike again. The Kwakiutl earthquake mask was undoubtedly inspired by magnitude 9 or greater earthquakes, events completely outside the realm of experience for millions of people who now call the West Coast of North America home.

They know from their elders' stories that monsters strike without warning. When the dancer appears, everyone feigns terror. The mask's movable visor alternately covers and uncovers his eyes.

In one telling of the story, a Kwakiutl man dances, his face covered by a cedar mask. At one midden near Namu, where a long-abandoned salmon cannery's wooden buildings now collapse into the sea and rot in the encroaching temperate rain forest, the broken shell fragments are nine metres deep a sign that here, and for roughly 10,000 years, Kwakiutl people lived and thrived.īut episodic events of unimaginable violence have been preserved in stories and artwork.

The deeper the layers of discarded mollusk shells, food remains, broken bits of stone tools and garbage, the further back in time such sites were used. They tell us that for thousands of years these were places where aboriginal people drew sustenance from the sea. Known as middens, such sites are archeological gold. coast, there are stretches of shoreline that lie buried under layers of bleached white and broken shells.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)